Could be deemed anti-competitive and might result in food price collusion among rivals

Consumers often assume that price freezes are always in their favour. However, it’s important to recognize that not all price freezes are equal, especially when it comes to products further up the supply chain. Every year, between Nov. 1 and Feb. 1, grocers request suppliers not to increase prices for undisclosed reasons.

Consumers often assume that price freezes are always in their favour. However, it’s important to recognize that not all price freezes are equal, especially when it comes to products further up the supply chain. Every year, between Nov. 1 and Feb. 1, grocers request suppliers not to increase prices for undisclosed reasons.

This unspoken agreement between grocers and suppliers, which likely started decades ago, may not ultimately benefit consumers. In October, as suppliers renegotiate contracts with grocers, prices are often adjusted, and many increase just before the three-month price freeze.

Now that the “blackout” period has ended, we should anticipate food prices rising again, as even Metro CEO Eric Laflèche himself warned consumers during his recent earnings call. Price hikes are likely to affect non-perishable products, primarily those in the centre of the store.

While high food inflation is certainly a concern for consumers, price volatility can be even more detrimental, and that’s exactly what these blackout periods bring to the market. Sudden spikes in food prices can surprise consumers and force them to temporarily abandon certain food categories, often including healthier options, leading to nutritional compromises. Once consumers perceive a food category as financially out of reach, it takes them a while to return.

In his efforts to stabilize food prices in Canada, françois-Philippe Champagne, the Minister of Innovation and Technology, should be aware of these blackout periods and target them as market-distorting mechanisms that ultimately harm consumers.

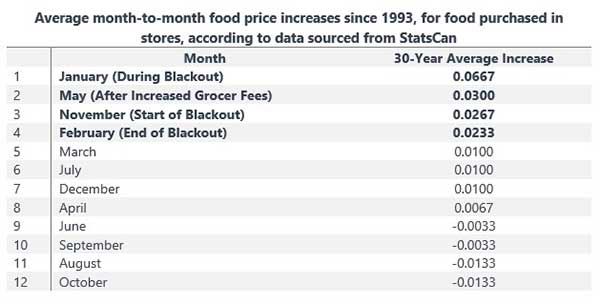

According to Statistics Canada, over the last 15 years, some of the highest month-to-month food price increases have occurred either in November or February. The highest month-to-month food price increase was in November 2008 at 2.5 percent, followed by February 2011 at 2.2 percent. Statistics Canada also recorded above-average month-to-month food price increases in November 2016 (1.6 percent) and November 2022 (1.7 percent). Despite the seasonality factor, blackout periods don’t shield budget-strapped consumers, as evidenced by increases in January 2016, January 2022, January 2020, and December 2018.

Coincidentally, these three months, January, February, and November, have experienced the highest month-to-month food price increases in the last 30 years, except for May. But we’ll get to that later.

The excuse often cited is that grocers don’t have time to deal with price changes during the busy holiday season. However, this argument may have been valid years ago when grocers manually updated prices on every item. Today, many prices are digital and displayed electronically, raising questions about the need for such blackout periods.

More fundamentally, since these blackout periods are industry-wide, one could argue that this practice could be considered anti-competitive and may lead to price co-ordination among competitors. Although we still don’t know the precise reasons behind past price-fixing scandals, blackout periods may indicate a broader culture of price-fixing in the industry, to the detriment of consumers.

This issue goes beyond blackout periods. Recently, Loblaw informed its suppliers that their fees will increase once again. In the agri-food sector, suppliers must pay grocers to do business with them. Distribution centre charges will rise from 1.17 percent to 1.22 percent, and direct-to-store delivery (DSD) charges will increase from 0.36 percent to 0.38 percent. While these may seem like minor changes to most of us, they can amount to millions of dollars for suppliers.

These yearly unilateral increases, imposed by Loblaw, will take effect on Apr. 28 without any dialogue or negotiation. While major multinationals like PepsiCo, Mondelez, Lactalis, Kraft-Heinz, and Kellogg may adjust their prices to offset higher fees from grocers, many smaller Canadian food manufacturers may struggle financially and even exit the industry. This results in higher prices and reduced competition, which is counterproductive for consumers.

Once again, by coincidence, May, the one month when we typically anticipate price hikes due to conflicts in the food supply chain, experienced the second-highest month-to-month average increase in the last 30 years.

To address these issues, we need more discipline and oversight, including the implementation of a mandatory code of conduct to ensure fair practices in the industry.

It’s time to put an end to this insanity.

Dr. Sylvain Charlebois is senior director of the agri-food analytics lab and a professor in food distribution and policy at Dalhousie University.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.