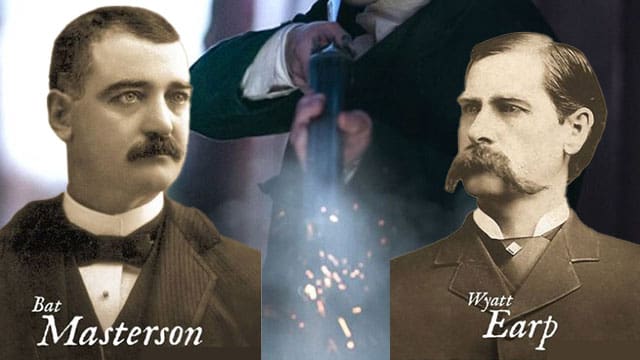

Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson were two of the Old West’s most famous lawmen, but their stories are far from simple

Just when you might think there’s nothing more to say, something pops up to prove that America’s Old West is the popular culture gift that keeps on giving. Called Wyatt Earp and the Cowboy War, the new six-part Netflix series is best described as a docudrama framed around the events that have come to be known as the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona, on Oct. 26, 1881. And it’s racking up impressive viewing figures.

Just when you might think there’s nothing more to say, something pops up to prove that America’s Old West is the popular culture gift that keeps on giving. Called Wyatt Earp and the Cowboy War, the new six-part Netflix series is best described as a docudrama framed around the events that have come to be known as the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona, on Oct. 26, 1881. And it’s racking up impressive viewing figures.

In addition to the specifics of the Earp/Cowboy War, the series places events squarely in the context of post-Civil War America where, for a couple of reasons, violent crime in Arizona, particularly highway robbery, was especially problematic.

Financier J.P. Morgan was attempting to buy troubled American railroads and required access to capital in the London market. But stories of mayhem and violence made potential investors nervous. And the U.S. government needed Arizona silver to pay off its Civil War debt.

In that environment, someone who helped pacify the territory by taking down the worst of the bad guys would be cut a fair amount of slack for questionable behaviour. And Earp needed all the slack he could get.

|

| Related Stories |

| Bat Masterson: The Canadian who helped tame America’s Wild West

|

| Wild Bunch showed True Grit in demythologizing the Old West

|

| The man who shot Billy the Kid

|

Earp was unusual for his time and context.

While other famous figures from the period came to violent ends at relatively young ages, he lived to two months shy of his 81st birthday, dying in his Los Angeles bed in 1929. Indeed, his only competitor in the Old West longevity stakes was his sometime gunfighter associate Bat Masterson, who – at the age of 67 – died from a heart attack at his New York City desk in 1921. By the way, Masterson was Canadian, born in Henryville, Que. in 1853.

On and off, Earp and Masterson worked together between 1876 and 1883, “cleaning up” Dodge City and Tombstone. They were temperamentally different, Earp being taciturn and largely abstemious whereas Masterson was gregarious and fond of a tipple. Still, the two men formed a personal bond.

Following the arrival of the railroad in 1872 and Kansas legislation squeezing out the competition, Dodge became the frontier’s premier “cow town.” Along with the money and itinerant cowboys in search of a rip-roaring good time, lawlessness abounded. Tom Clavin’s Dodge City neatly captures the town’s ambience: “It was reported in 1879 that there were seven hundred residents, 14 saloons, two dance halls, and four dozen prostitutes.”

Tombstone, in contrast, had much more to it than violence and the notorious Boot Hill. Thanks to the plentiful silver in the surrounding hills, it was an affluent outpost in the desert.

City historian Don Taylor, in Tombstone, the First Fifty Years: 1879 to 1929, notes that telephones arrived by 1882. By 1883, Tombstone had two gas companies, three water companies, five ice cream parlours, and fresh seafood delivered daily from Mexico’s Baja.

Earp and Masterson can be described as complicated figures with unconventional pasts. Earp, however, was much more ambiguous morally.

To quote conservative journalist and author Kevin Williamson: “Wyatt Earp the historical figure was a pimp, a cheat, a claim-jumper, probably a horse thief, and a cold-blooded murderer … He had an arrest record as long as your arm and continued as a career criminal into his old age, from fixing boxing matches to fixing card games.”

The “murderer” accusation relates to what’s known as the “vendetta ride,” which Williamson characterizes as Earp abusing “his badge to carry out extrajudicial executions when the legal system didn’t give him the outcome he wanted.”

Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson both enjoyed long post-lawman lives, far away from Dodge and Tombstone.

Earp went west, eventually settling in Los Angeles. His activities included gambling, real estate, saloon keeping and mining. But while there were lucrative paydays, his financial circumstances mostly tended to the modest side.

In his later years, he sometimes acted as a technical adviser on silent western movies. Two of the genre’s biggest stars – William S. Hart and Tom Mix – were pallbearers at his funeral.

Masterson had various adventures as a gambler, saloon keeper and boxing promoter before moving to New York City in 1902. Once there, he parlayed his convivial personality, reputation and past friendships into a new life as celebrity journalist and man-about-town. By the time he died, his popular column – Masterson’s Views on Timely Topics – had generated at least four million words.

Perhaps the worst that can be said of Bat Masterson is that he had the soul of a con man. But Earp’s bottom line is much dicier.

Was Wyatt Earp a righteous lawman or a career criminal?

I suspect the answer is both, even at the same time. And if righteous is an inappropriate term, substitute fearless instead.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.